Counting the rays of the sun: outdoor HDRI

Vadim Lebedev

29 July 2022

29 July 2022

in3D offers app and SDK for 3D body scanning. With in3D app, anyone can create their realistic 3D avatar with just a phone camera within 30 seconds. in3D avatars have Mixamo-compatible rig and 2048×2048 texture. Try our app now or learn more about our SDK. Contact us for more details.

In in3D, we sometimes train neural networks on synthetic data, mostly the renders of human faces and bodies. A good way to model natural lighting conditions for realistic render is a spherical high dynamic range image (HDRI). We use Insta 360 One X camera to capture spherical images for the specific conditions that we are interested in, and then combine multiple expositions into a single HDRI in Photoshop. What we usually want to capture is indoor lighting, because our clients mostly live and make their scans indoors.

However, for the purposes of having fun, I decided to take the camera on my vacation and try some outdoor HDRIs. Who knows, maybe a swamp creature would like to scan with our app one day, we have to be ready.

However, for the purposes of having fun, I decided to take the camera on my vacation and try some outdoor HDRIs. Who knows, maybe a swamp creature would like to scan with our app one day, we have to be ready.

Same goes for the river dwellers:

and there’s no doubt we have to be prepared to function in the conditions like this given current political climate:

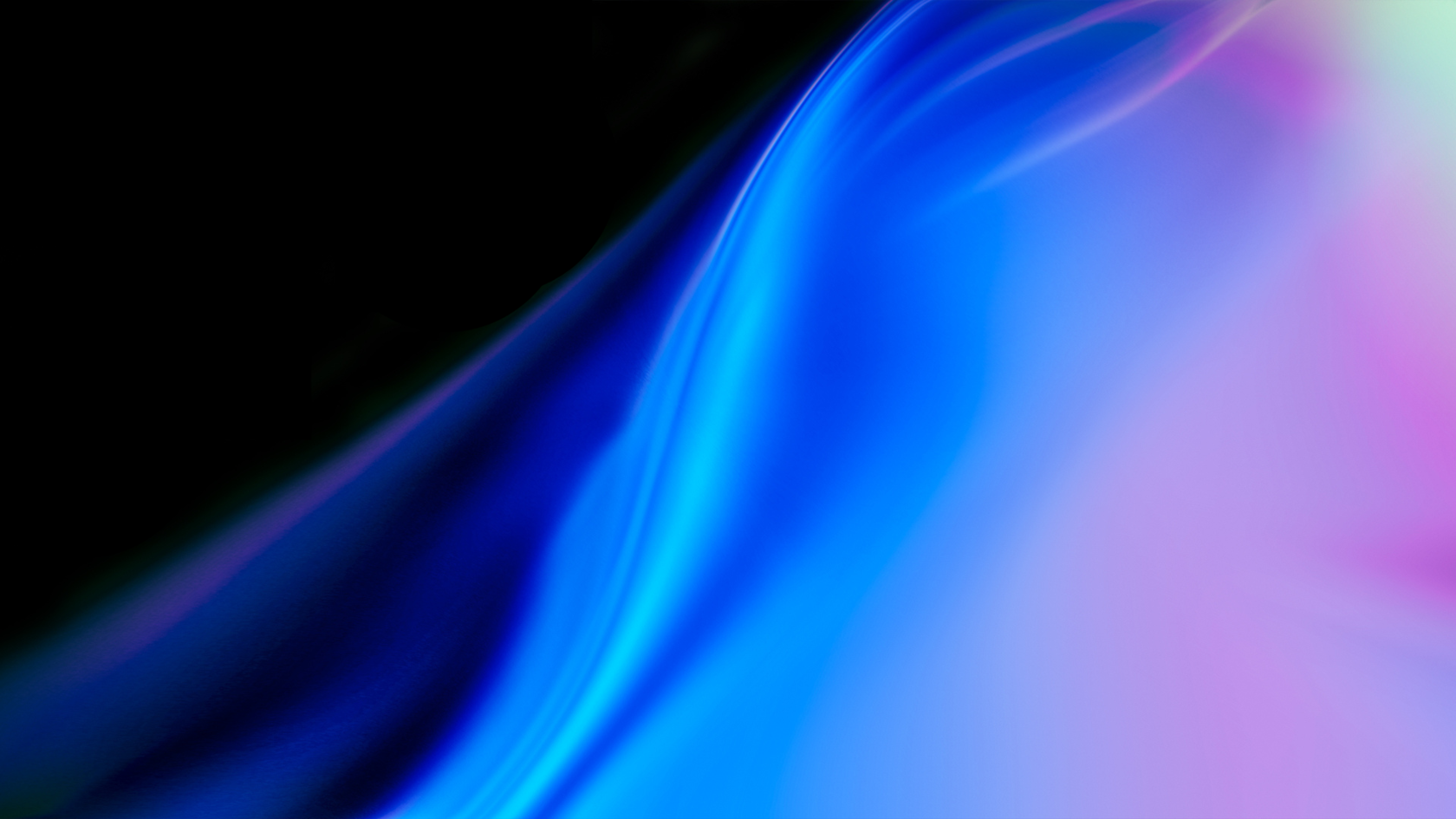

However, one thing attracts attention when making renders with this HDRIs: there are almost no shadows, even when the skies are clear and the sun shines brightly. It is especially striking when making comparison with more professionally made HDRI like this:

Source: https://polyhaven.com/a/fouriesburg_mountain_midday

This is a render (Blender, Cycles engine) with our sunlit outdoor HDRI and another render with HDRI from polyhaven.

Where did the shadows go? Apparently, the lowest exposure available to our camera is not low enough to properly capture the luminance of the sun, and the image gets saturated at much lower level. That is not a novel problem as sun is notoriously bright and there is even a special blender addon to fix it. Alternatively, we can just put a bright blob on our HDRI at the location where the sun should be and get much better result:

One question still stands. Do we believe that sun as depicted on HDRIs from polyhaven is accurate and can be used as a reference, or was it created in post-processing, maybe inaccurately? I believe the closer look into it reveals the truth:

What we see here is the light scattering on the edges of the main lens of the camera (or whatever covers the main lens). It is the same effect that we all have seen on the recently released images from the James Webb Space Telescope:

James Webb uses hexagonal mirrors, and every edge produces rays in two opposing directions, but the rays from the opposing edges coincide, so we get six rays total. For odd number of edges, there would be twice as many rays as edges. Now, I’m no expert in digital cameras, but Wikipedia entry on optical diaphragms has 5-blade diaphragm as one of examples, so it must be a common kind.

Five blades would give the same picture with 10 rays that we observe in reality. It shows that the sun on HDRI is indeed real, and it can be used for physics-based rendering. Probably, this HDRI was combined from multiple shots made by a regular DSLR camera that can close its diaphragm and so get lower expositions compared to our spherical camera.

What we’ve learned today:

What we’ve learned today:

- Do not trust HDRI data blindly in presence of bright light sources

- You can determine a camera type by counting the rays on the photo

- Poluhaven’s outdoor HDRIs are actually good and there was no practical reason to wander into swamplands to make new HDRIs